Carl Pulfrich and the Universal Refractometer

On Optics and Other Inventions: The Experimental Life of Carl Pulfrich

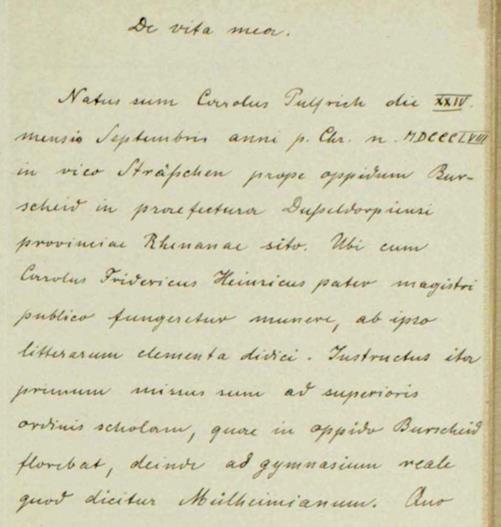

The rare occasions on which we encounter the name “Pulfrich” are most often in reference to a particular optical phenomenon associated with stereoscopy: the Pulfrich effect. This striking effect concerns human vision, whereby an object moving along a straight line is perceived as if receding or advancing in depth, thus creating the vivid impression of three-dimensional motion. Beyond this celebrated phenomenon, Dr Carl Pulfrich (1858–1927) (Figure 1) made significant contributions to both theoretical and experimental physics. His research embraced problems of optics, thermodynamics, and climatology, while he also devoted himself to the design and construction of numerous precision instruments—most of them intimately connected with the science of optics.

Figure 1. Photograph of Carl Pulfrich in Bonn during the year 1889

(https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Carl_Pulfrich.JPG)

Among Pulfrich’s instruments, the Universal Refractometer stands as his true masterpiece: for decades it remained the benchmark of precision and accuracy in the measurement of refractive indices, distinguished by its remarkable versatility in working with both solids and liquids. Our inquiry into the life and work of Carl Pulfrich begins precisely with this instrument, preserved today in the historical collection of scientific apparatus at the Department of Chemistry and Industrial Chemistry of the University of Pisa (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Universal Refractometer devised by Pulfrich, part of the collection of the Dipartimento di Chimica e Chimica Generale (DCCI) of the Università di Pisa.

Pulfrich had the opportunity to collaborate and to form close associations with some of the most eminent physicists of his age, beginning with his mentor Rudolf Clausius, and later including Max Planck, Heinrich Rudolf Hertz, Ernst Abbe, John Alfred Brashear, George Hale, and others. From the letters preserved in various archives, there emerges the portrait of a man of great energy and generosity, ever eager to share his passion for experimentation and his commitment to devising increasingly refined instruments, capable of satisfying the intellectual curiosity of his interlocutors.

His education and professional development are recounted by Pulfrich himself (Figure 3). In 1889, after completing his doctorate in physics at the University of Bonn, he applied to the same university for appointment as Privatdozent.

Figure 3. From the archives of the University of Bonn, UAB_PF-PA 421_Pulfrich, Carl. Foglio cinque, recto.

Fortunately, this document is still preserved in the university archives, and it has been possible to consult the original. Translating from the Latin, we read: “I, Carl Pulfrich, was born on 24 September 1858 in the village of Sträschen, near the town of Kurscheid, in the province of Düsseldorf, in the Rhineland. There, while my father, Charles Friederieur Heinrich, served as a public-school teacher, I learned the rudiments of literature. There I received my early education. After preparing for my journey, I was first sent to the higher school located in the town of Burscheid, and then to the Realschule, called the Mülheimianum Gymnasium. After completing my studies in one year, I proceeded to the alma mater of the university, the Friedrich Wilhelmine at Thenn, to pursue studies in mathematics and physics, and I also happened to study philosophy.”1

Even from these few words, we may discern that Pulfrich’s education bore the hallmark of the Humboldtian model, so named after Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767–1835) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Post stamp portraying Wilhelm von Humboldt, from and original lithograph by Franz Krüger

This model of education was conceived in the Kingdom of Prussia between 1809 and 1810, with the aim of reforming the entire educational system—from elementary schools through secondary education and up to the highest level of academic training.2 The principal purpose of these Prussian reforms was to revitalise and modernise the state, animated by a spirit of revanche after the defeat suffered in the Napoleonic wars (and thus, one might say, from the need to create a system distinct from the French model).

In pursuing this goal, policies were introduced that we might already describe as socialist in character: the abolition of serfdom, the freedom of enterprise and employment, the self-government of cities through elected representatives, and, crucially, the education of children. Citizens, no longer bound as serfs, were to be free to cultivate their talents according to their own sense of responsibility. In this way, it was envisaged that they would generate new resources for the state and for the nation.3

This system is regarded by many as the principal reason for Germany’s extraordinary intellectual flowering from the latter half of the nineteenth century into the twentieth. From the Humboldt University alone, twenty-nine Nobel laureates emerged, and the model continues to inspire numerous institutions worldwide.

The Gymnasium attended by Pulfrich belonged to this tradition, seeking to offer students a broader humanistic education rather than merely training them according to the expectations of their social rank.4 For Humboldt, anyone who possessed a general, enlightened formation in the humanistic and civic sense—whether artisan, merchant, soldier, or civil servant—could acquire the specialised knowledge required for any profession, while at the same time preserving individual freedom.5 This new interpretation is encapsulated in the word Bildung, the holistic development of a person’s individual capacities through freedom and self-determination.

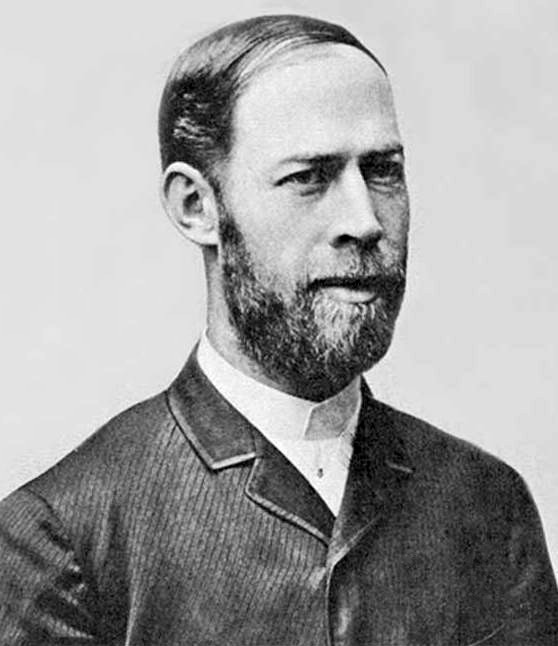

Carl Pulfrich embodied Humboldt’s hopes with remarkable fidelity. He studied literature, Greek, and Latin before devoting himself to physics and, in particular, to optics—his doctoral thesis concerned photometric studies on the absorption of light in isotropic and anisotropic media.6 His patriotic spirit then led him to enlist 7 as a Boummer in the infantry (II Battalion, Regiment No. 28), eventually attaining the rank of military tribune (Offizier). In that moment of confidence and hope in the Prussian state, it was by no means unusual to serve the nation as a soldier. Others close to the newly graduated Carl Pulfrich made similar choices, among them the eminent Rudolf Clausius (1822–1888) (Figure 5), who himself had taken part in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870.8

Figure 5. Photograph of Rudolf Clausius in 1888 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Clausius.jpg).

Clausius appointed Pulfrich as his assistant, and also served on the committee that granted him the licence to teach as a Privatdozent. When Clausius passed away in 1888, it was Carl himself who took charge of his mentor’s manuscripts in order to complete the edition of Die Mechanische Wärmetheorie,9 working together with a contemporary of his own generation, a pupil of Kirchhoff and Helmholtz—the illustrious Max Planck (1858–1947).

Apart from the preface left to us by these two great physicists, no other sources survive that describe the nature of their collaboration or the extent to which they contributed to the third volume of Clausius’s monumental work, the Die Kinetische Theorie der Gase. What is certain, however, is that they laboured together to incorporate Maxwell’s mechanical-statistical treatment, as Clausius himself had wished before his death.10

From this episode we may begin to grasp the breadth of Pulfrich’s intellectual formation: he was not only capable of addressing problems of optics (as evidenced by his thesis on the absorption of light, which also considered the behaviour of lenses and prisms), but also matters of thermodynamics and statistical mechanics.

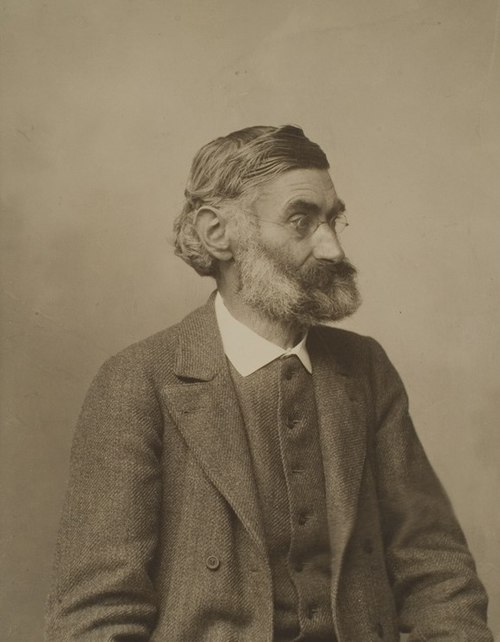

Thus, at barely thirty years of age, Pulfrich found himself engaged in editing Clausius’s text alongside one of the most active physicists in Germany at the time. Simultaneously, he retained his position as assistant to the newly appointed professor, Heinrich Rudolf Hertz (1857–1894) (Figure 6), who, as it happens, was also his brother-in-law.

Figure 6. Photograph portraying Heinrich Rudolf Hertz taken in 1894 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Heinrich_Rudolf_Hertz.jpg).

Carl Pulfrich and a New Type of Refractometer

At this juncture, an event occurred that would change the course of Pulfrich’s life and lead him away from an academic career. His publication Das Totalreflectometer und das Refractometer für Chemiker,11 on a new type of refractometer,12 attracted the attention of a prominent figure in the field of scientific instrumentation: Ernst Abbe (1840–1905) (Figure 7)13, who had risen to the directorship of the Carl Zeiss company.

Interest in refractometers had grown considerably after the Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1893, at which Carl Zeiss had exhibited numerous optical measuring instruments.14 On that occasion, as on others, Zeiss pointed out that refractometers could be employed to distinguish among a wide range of substances, to determine their degree of purity or alteration, and to establish the percentage or concentration of many solutions and mixtures. More importantly, unlike other instruments, the refractometer could be used without prior knowledge of optics, and required no particularly intricate manipulations in order to operate effectively.

Figure 7. Photograph of Ernst Abbe taken in 1904 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ernst_Abbe_(HeidICON_29803)_(cropped).jpg).

We must bear in mind that, in the second half of the nineteenth century, techniques for determining the structures of organic chemical substances fell into three main categories:

- Direct analysis;

- Optical analysis;

- Spectroscopic analysis.

The first of these approaches was based on the fundamental assumption that the basic structures of many compounds were already known, and it had been strongly advocated by Jacobus van’t Hoff in 1878. The use of the spectroscope for such purposes was promoted by the English chemist Walter Hartley in 1879, though in this case too, a profound knowledge of material behaviour was required.

By contrast, optical analysis, primarily based on refractometry or polarimetry, could be conducted simply by employing the appropriate instruments and comparing the measurements obtained with reference tables. Both refractometers and polarimeters thus became widely used instruments, extending far beyond the confines of university or highly specialised laboratories.15

It is therefore easy to imagine that Ernst Abbe made Pulfrich a highly attractive financial offer, immediately appointing him head of the laboratory for the design of measuring instruments. Pulfrich consequently severed his professional ties with the University of Bonn, and from that moment until his death he remained associated with the renowned scientific instrument company Carl Zeiss.16 From that point on, his instruments were also manufactured and commercialised by the firm, greatly facilitating their dissemination.

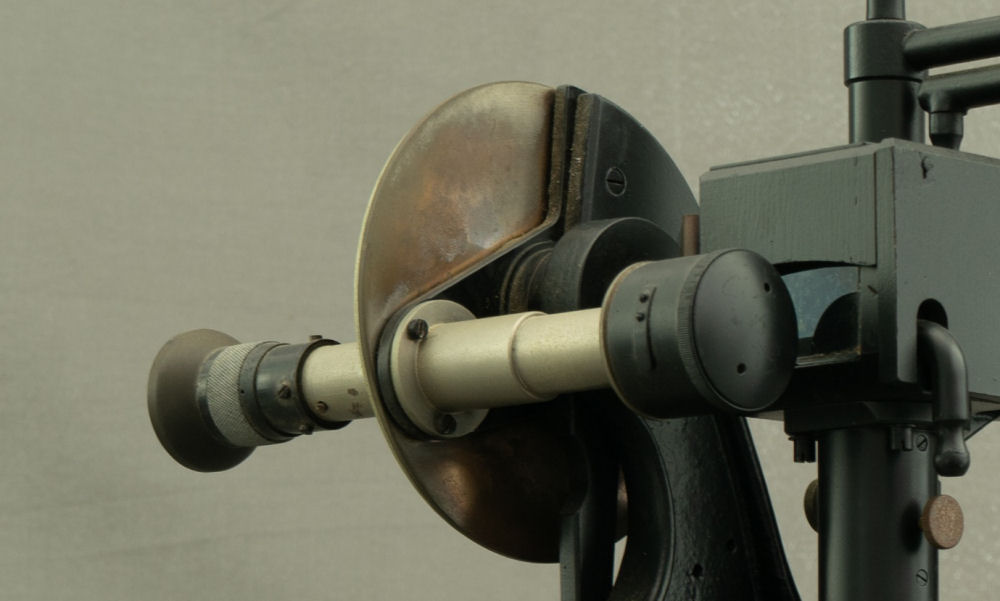

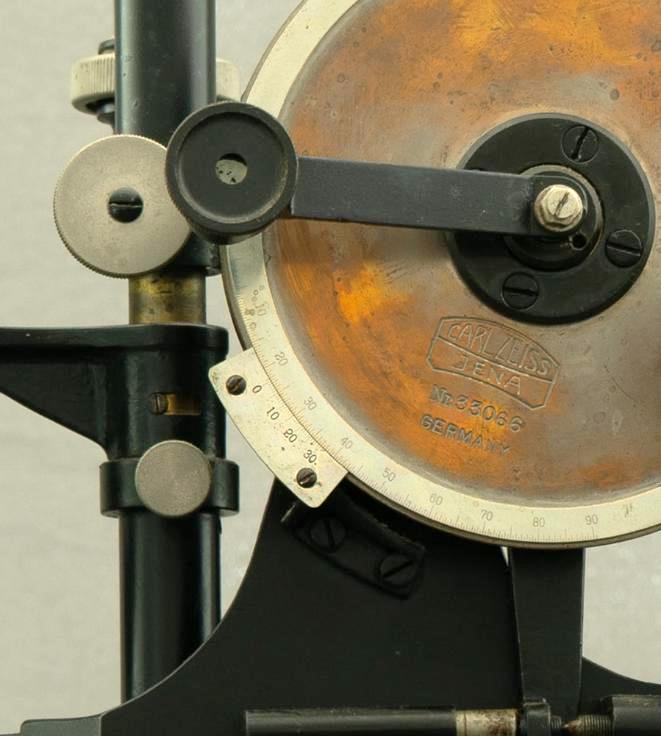

One of his Universal Refractometers is still preserved today at the Department of Chemistry and Industrial Chemistry of the University of Pisa (Figure 8).17

Figure 8: Photo of the Universal Refractometer devised by Pulfrich, part of the collection of the Dipartimento di Chimica e Chimica Generale (DCCI) of the Università di Pisa

The instrument bears the serial number 33066 and can be dated to around 1925. It is accompanied by an instruction manual, in both English and French, which describes its operation, maintenance, and provides tables showing the variation of the prism’s refractive index with temperature.18

Operation and Description of Pulfrich’s Universal Refractometer

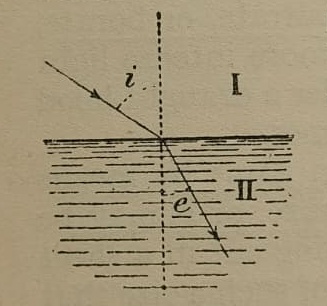

The operating principle is, of course, based on the refractive index: when a beam of monochromatic light passes from a less dense medium (I) to a denser medium (II), its trajectory is deflected, as illustrated in Figure 9. The two angles formed by the beam with the normal to the interface ‘i’ for the incident beam and ‘e’ for the refracted beam—depend on the refractive indices of the two media.19

Figure 9: Drawing of the principle of refraction as described inside the manual of instruction given with the instrument by the producer Carl Zeiss.

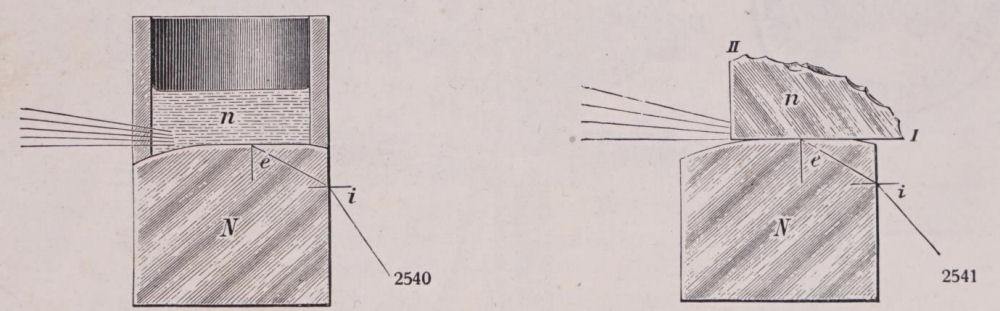

The most important component of this instrument is a 90° prism, cut from a high-refractive-index glass (Figure 10). One face of the prism is horizontal and oriented upwards. This face is placed in contact with the substance under investigation, whether liquid or solid. The second face of the prism is vertical, and it is through this surface that one can observe the limit of light passing through the prism according to the grazing angle of incidence (the critical angle of refraction).

With the aid of an eyepiece and a graduated circle, it is possible to read the angle i at which the critical ray emerges from the vertical face of the prism. Knowing the refractive index of the prism (N), one can then determine the refractive index n of the substance under examination using the corresponding relationship:n= √(N2-sin2 i).

Figure 10: Schematization of the working conditions of the instruments with fluids, on the left, and solids, on the right. We can clearly discern the behaviour of the ray of light (here represented by some lines) when it passes first through the sample and after through the 90° prism. From the prisms it goes to the optics that allow us to make the measurement.

The fact that the refractive index of a substance varies with temperature was established by Gladstone and Dale in 1863. Pulfrich’s instrument allows for precise control of the operating temperature. A beam of monochromatic light, for example emitted by sodium, could be readily produced by heating a chloride, bromide, nitrate, or borate of sodium over a Bunsen flame.

However, the instrument was designed primarily for the use of a Plücker tube filled with low-pressure hydrogen. The development of such tubes is closely associated with Bonn, Pulfrich, and Hertz. Electrical discharges in rarefied gases had been studied by Hittorf, Geissler, Kayser, Plücker, and others, all in Bonn. In 1859, Plücker investigated the phenomenon of fluorescence produced by cathode rays on the glass walls of the discharge tube; this line of research would later be advanced by Crookes.20

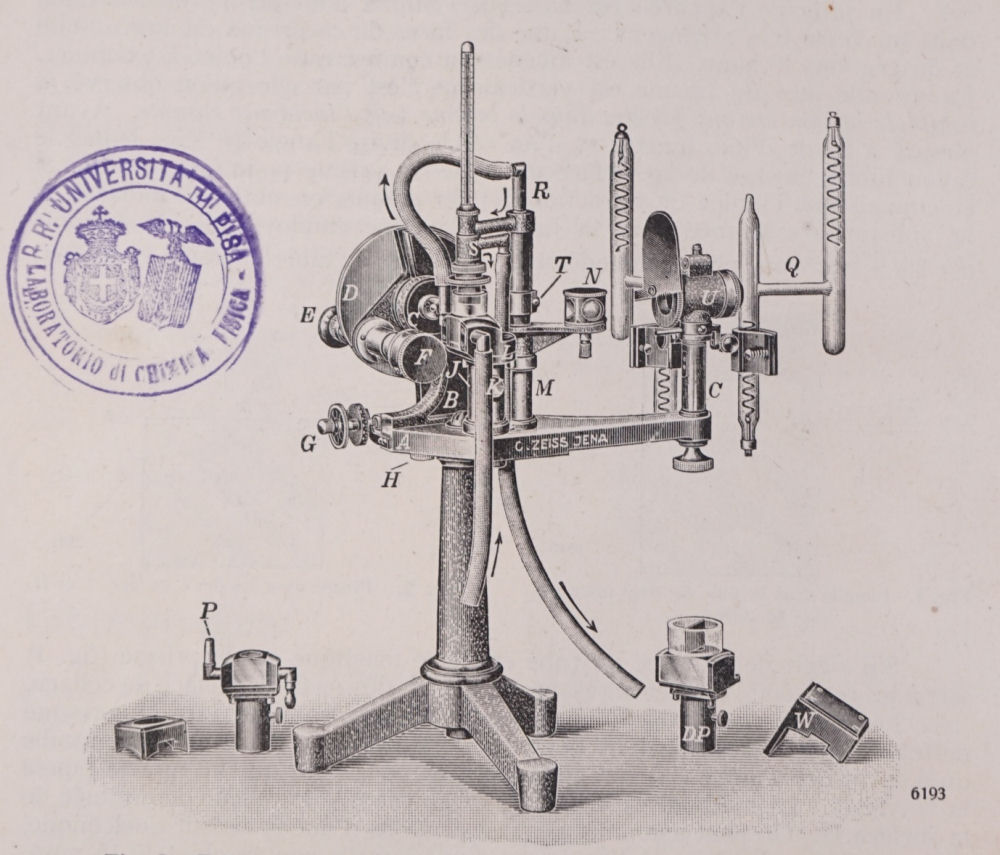

In the instruction manual, the instrument is illustrated with a Plücker tube (Figure 11) as the light source (marked with the letter Q).

Figure 11: Schematic representation of the Universal Refractometer by Pulfich as described inside the manual of instruction given with the instrument by the producer Carl Zeiss.

To use a sodium lamp, it is recommended to position the instrument at a distance of approximately fifty centimetres from the light source, with the reflecting prism (N) placed on the opposite side. The 90° prism (L) supports the liquid cell and should be set in the resting position—that is, positioned as low as possible and then secured by tightening the screw (K). The vertical face of the prism must be oriented towards the eyepiece (F) (Figure 12).

One of the distinctive components of this refractometer is the temperature control system. A rubber tube is inserted at position (R), with the other end attached to the prism cell. A thermometer is screwed into position (S) above the sample. A thermostatic bath is connected at (L), through which water circulates and is then discarded after passing through the system.

Figure 12: Detail of the eyepiece (F) positioned after the prism to receive the light refracted by the vertical side.

After passing through the prism, the light traverses an eyepiece, which can be adjusted from position (F). The eyepiece is rotatable, but there are four fixed positions that can be easily perceived during rotation, corresponding to four specific conditions. In one position, the eyepiece is fully open; in two others, it is half-open; and in the fourth, it is completely closed. The half-open positions are used when observations are made with a divided cell, while the fully open position is employed for a single cell.

The eyepiece is secured to the disk (D), which features a graduated scale covering one-quarter of its circumference, marked in degrees and half-degrees (30’) (Figure 13). A vernier with thirty divisions is also present, allowing the reading of each single minute. The vernier reading is facilitated by a small movable lens, which can be positioned in front of the graduated scale.

Figure 13: Detail of the graduated disk with the vernier scale. The small lens has been moved to show the marking on the disk.

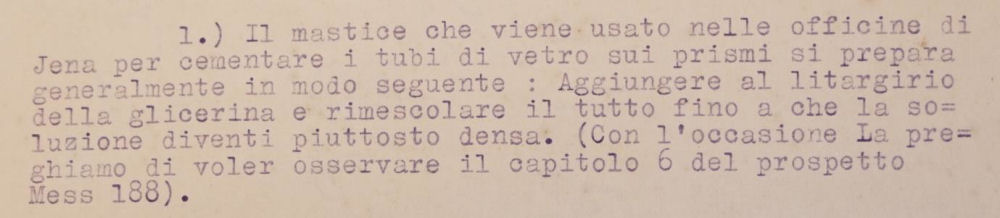

Inside the collection of the University of Pisa, a 1928 letter has been recovered, written by the Professor of Physical Chemistry, in which he requested clarification from Carl Zeiss regarding how to attach the liquid cell to the prism. This detail is particularly interesting, as the company’s reply reveals the chemical composition of what was referred to as the prism cement (Figure 14).

Figure 14: Detail of the letter found in the Archive of the Università di Pisa, written by the head of the General Chemistry Laboratory to the workshop of precision instruments making of the Carl Zeiss factory in 1928.

What is particularly interesting is that the literature proposes several different mixtures for the same purpose. In Alexander Findlay’s Practical Physical Chemistry,21 it is suggested to use isinglass or, if the operating temperature is low, vaseline. Similar recommendations appear in other contemporary manuals. From certain articles, we also know that Pulfrich himself recommended a different procedure, namely the use of mercury-barium double iodide,22 also known as Rohrbach’s liquid. At present, the reasons for these various formulations remain unclear, but they demonstrate that different substances and mixtures were tested by various users of this instrument.

Another aspect of interest relates to the history of refractometers. Although this Universal Refractometer was highly versatile, allowing accurate measurements of both liquids and solids, it did not remain long in material analysis laboratories. It was eventually replaced by simpler, though less versatile, instruments. Today, many laboratories possess the so-called Abbe refractometer, of which several functioning examples remain at the Department of Chemistry and Industrial Chemistry, along with a historical instrument in the scientific instrument collection.23

It is also noteworthy that modern refractometers, though far more compact and equipped with digital readers, are based on the same physical principle, clearly visible in historical instruments such as Pulfrich’s Universal Refractometer. This continuity underscores their enduring educational value.

References, notes and links:

1. “UAB_PF-PA 421_Pulfrich, Carl,” preprint, University of Bonn, 1889.

2. Bongaerts, Jan C. 2022. “The Humboldtian Model of Higher Education and Its Significance for the European University on Responsible Consumption and Production” 167 (10): 500–507.

3. Boria, Francesco, and Barbara Rapaccini. 2018. “Education and Research: The Development of German Physics in the Nineteenth Century—Part One.” Lettera Matematica 6 (3): 161–66.

4. An interesting point is that mathematics, after prolonged debate, had been relegated to a secondary role. This was because its relative “schematicity” and “simplicity” appeared to reduce the complexity of life and human emotions to mere numbers, and was therefore poorly suited to a perspective that sought to celebrate the Renaissance ideal of the human being.5. Wilhelm von Humboldt: Schriften zur Anthropologie undGeschichte.– Werke in fünf Bänden, vol. 1. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Flitner, A., Giel, K. (eds.) Darmstadt (1964).

6. He defended his thesis the 18th of June 1881, graduating with the highest honours.

7. He could have been exempted from military service due to his position at the university.

8. Cahan, David. 1985. “The Institutional Revolution in German Physics, 1865-1914.” Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences 15 (2): 1–65.

9. Clausus, Robert. 1887. Die Mechanische Warmetheorie. Edited by Max Plank and Carl Pulfrich.

10. Jungnickel, Christa, and Russell McCormmach. 2017. The Second Physicist. p.22.

11. Pulfrich, Carl. 1890. Das Totalreflectometer Und Das Refractometer Fur Chemiker. Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann.

12. The refractometer could have been bought from Max Wolz a Bonn.

13. Ernst Abbe was undoubtedly another physicist of extraordinary importance. To him we owe the resolution of numerous optical problems, the invention of apochromatic lenses, the Abbe condenser, and the introduction of the Abbe number, which quantifies the variation of refractive index with wavelength for any transparent material. He is also credited with the discovery of the Chi-square random variable. Abbe repeatedly declined highly prestigious positions at various German universities in order to remain with Carl Zeiss

14. Deborah Jean Warner, Chapter 3: Refracometers and Industria Analysis, in: Morris, Peter, and Klaus Staubermann, eds. 2008. Illuminating Instruments. Studies in the History of Science and Technology. p.44.

15. Jensen, William B. 2003. Philosophers of Fire: An Illustrated Survey of 600 Years of Chemical History for Students of Chemistry. Oesper Collections. University of Cincinnati. p. 152.

16. The company founded by Carl Zeiss, which still bears his name today, was at the forefront of optics and precision measuring instruments; a position that maintains still today.

17. https://ricerca.dcci.unipi.it/instrument-museum.html

18. Gladstone e Dale, XIV. Researches on the refraction, dispersion, and sensitiveness of liquids". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 153: 317–343. 1863-12-31.

19. Usually this important relation is called Snell’s Low

20. Appelyard, Rollo. 1927. “Pioneers of Electrical Communication - Heinrich Rudolf Hertz.” Electrical Communication 6 (2): 63–77.

21. Findlay, Alex. 1920. Practical Physical Chemistry. London: Longmans, Green & Co.

22. Pulfrich, Carl. 1890. Das Totalreflectometer Und Das Refractometer Fur Chemiker. Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann.

23. https://ricerca.dcci.unipi.it/rifrattometro-abbe.html

CREDITS: LUCA ROCCA E VALENTINA DOMENICI